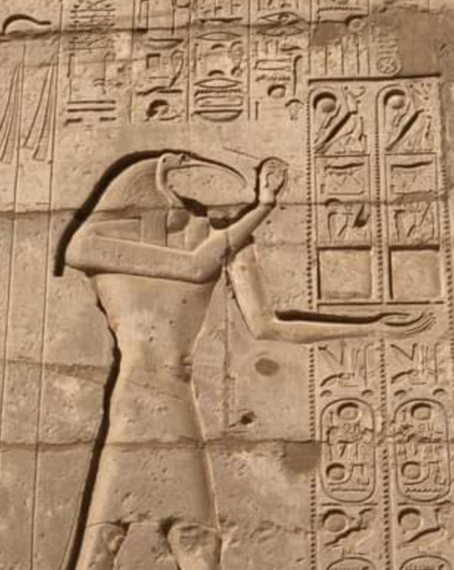

Exodus 7–10, Part 1

Some teachers are popular because they are easy. Some are popular because they are interesting. Tom Olbricht was certainly not an easy teacher, and his methods of presentation were not always very interesting. Yet he was fairly popular, at least with the more studious graduate students. Tom Olbricht was popular because he had something worthwhile to say. He attacked some of the common beliefs we had grown up accepting. He was not always right, but one belief he attacked relentlessly and effectively was the conventional idea that “the God of the Old Testament is a God of wrath, while the God of the New Testament is a God of love.”1

All parts of the Scriptures testify both to the love and severity of God. The Old Testament story of Nadab and Abihu being killed for offering unauthorized worship (Leviticus 10) is matched by the New Testament story of Ananias and Sapphira being killed for attempting to lie to the church (Acts 5). The New Testament story of the prodigal son is balanced by Hosea’s relationship with his wife. God’s love as well as his severity was demonstrated in the Mosaic era (Exodus 34:6-7). His severity as well as his love is taught in the New Testament era (Romans 11:22). In both testaments, God is love. In neither testament is his love mushy, weak permissiveness. Such emotionalism is wrongly called love. The New Testament has a manger; it also has a cross (Luke 9:23). The Old Testament has the deliverance of Israel at the Red Sea, but the Egyptians are drowned in that same event.

Many people do not like the idea of the plagues, especially of the last plague. But we need the lessons of the plagues as much today as when the events happened.

Nature Is Not God

Perhaps the first lesson of the plagues is that nature is not God.

The Egyptians worshiped the Nile. They worshiped cattle. They worshiped the Sun. The plagues showed that the Lord was over all of these.

Because people worshiped nature, they did not advance scientifically. People who worship nature are afraid to interfere with nature. Biblical religion taught people that nature is not a god to be worshiped. We should not speak of “mother nature.” Nature is not our mother. It was not nature that brought us into being. God brought all into existence. In teaching thus, biblical religion prepared the way for scientific advancement that had been hindered by nature religions.

Today we are in grave danger of reversing the progress. Christianity has been slandered as the enemy of science. As a result of this slander, superstitions are creeping back into the mainstream of life. Nature worship has made a major comeback. This is not a small matter. It is disrespectful toward God (Exodus 20:3-4). It leads to disrespect of human life. It leads to the perversion of natural relationships (Romans 1:22-23). Ultimately, it will halt the real progress of science, as science (viewed as a god) will be used to oppress rather than to serve mankind. Science has often been a great servant to mankind. But science taken as an all-encompassing master is a slave-master.

Government Is Not God

The plagues also showed that government is not God.

The Egyptians, like many ancient people, worshiped their ruler as a god. His rule was virtually unlimited. It took a long time for the biblical idea of limited government to take hold, but eventually it did take hold. Saul, the king, had to listen to Samuel, the prophet. David, the king, had to listen to Nathan, the prophet. John the Baptist confronted King Herod.

We often overlook this aspect of the story in Exodus; but historically it was of great importance. The biblical account of the struggle between Israel and Pharaoh, as it was presented in the Geneva Bible, was one of the main reasons why King James wanted a new translation of the Scriptures. Puritans, pointing to the midwives disobeying Pharaoh as it was presented in the Geneva Bible, felt that they were justified in disobeying their earthly king if he overstepped his proper sphere.2 King James wanted a new translation of the Scriptures that would justify him as a totalitarian ruler.3

The Bishop who headed King James’ translation project chose the translators carefully – assigning those with Puritan leanings either to the apocryphal books or to parts of the Bible where this issue of the extent of a king’s authority would not come up. But still, the truth could not be hidden. The Bible (even in the KJV) does not support the idea of an absolute monarch, or of any form of government with absolute power. The government is to have limited powers (see Romans 13). If a government oversteps those proper powers it forfeits the right to rule.

Pharaoh would have been respected if he had kept to his proper sphere (Romans 13:1–2; Titus 3:1; 1 Peter 2:13–14). But in demanding that his authority be recognized in all aspects of life he lost his right to rule and ultimately his right to live (see Acts 5:29).

Christians today should not be asking the government to do more and more. We should not be needlessly disrespectful of government, but we ought to be striving to keep government limited to its proper sphere. Every new role the government takes on is one more responsibility taken from either the family or the church. The lack of respect shown to family and church today correlates directly to the usurping of the roles of these two institutions by the government. It is bad enough that this happens. It is far worse that some Christians encourage it.

Words Are Not Repentance

God is not to be trifled with; mere words are not repentance. One can confess sin, one can express the intention to repent verbally, but acceptable repentance has not happened until action is taken. And the action taken must be of the proper kind. It must be a sincere attempt to reverse the wrong done. Pharaoh repeatedly promised to change his ways, but he did not ever truly repent of his arrogant pride (Exodus 8:8, 15, 28–29; 9:27-28, 34–35; 10:16).

Effective repentance must be a real reorientation of life toward God. That is a clear lesson of the plague account, and it is repeated in the New Testament. John warned those who claimed to be repenting that they must bring forth fruit in keeping with repentance (Lk 3:7–8). Jesus is effectively saying the same thing when he warns, “No, I tell you; but unless you repent, you will all likewise perish” (Luke 13:3). Charles Spurgeon once used seven texts in one sermon. The topic of the sermon was the tendency of some to make false professions of sorrow for their wrongs. On the one hand Spurgeon spoke of the insincere confession of Pharaoh (Exodus 9:27), the double-minded confession of Balaam (Numbers 22:34), the eleventh-hour confession of Achan (Joshua 7:20), the unstable confession of King Saul (1 Samuel 15:24), the despairing confession of Judas (Matthew 27:4). On the other hand he noted the humble confessions of Job (Job 42:6) and of the prodigal son (Luke 15:18).

Nature is not God. The government is not God. We are not God. We need to reorient our lives toward God and away from the things we have been pursuing.

The Lord may not send us these same ten plagues if we fail to do so, but we will not enjoy his fellowship as we could, unless we truly repent.

To be continued…

Matsapha, Eswatini, Africa

1 See Thomas Olbricht, He Loves Forever, page 12.

2 The Geneva Bible included footnotes that King James found extremely upsetting. Commenting on Exodus 1:19, the footnote stated “Their disobedience herein was lawful ….” A number of other footnotes referred to Pharaoh as a tyrant.

3 See also F.F. Bruce, The English Bible: a History of Translations, pp 96-97; Alister McGrath, In the Beginning: the story of the King James Bible…, pp 149-171; and Jack Lewis, The English Bible from KJV to NIV pp 9-68.