When it comes to our personal reading of the Bible, most of us have parts we find harder to get through. Certain prophecies can be challenging. Levitical laws can be confusing. But for a lot of people, the hardest parts of Scripture are the genealogies.

Long lists of names rarely feel compelling. Name follows name, and before long our eyes glaze over. And yet we know those genealogies are not there by accident. God does not waste ink. Every name and every generation is part of the story He has been telling from the beginning, a story of faithfulness and redemption that has never gone off track.

That is especially true of the genealogy that opens the New Testament. Matthew begins his Gospel this way: “The book of the genealogy of Jesus Christ, the son of David, the son of Abraham” (Matthew 1:1).

That opening line is deliberate. Before Matthew tells us what Jesus did, he wants us to understand who Jesus is and how He fits into the story God has been working out since the very beginning. So the question we need to ask is a simple one: What does a list of names reveal about God’s plan?

One of the first things this genealogy makes clear is that the Gospel is grounded in real history. Matthew is not dealing in symbols or abstractions. He is anchoring the story of Jesus in real people, real places, and real events. The Christian faith is not built on inspiring ideas or carefully crafted myths. It is built on what God has actually done in history.

Matthew traces Jesus’ lineage from Abraham through David, through the kings of Judah, through the exile, and finally to Joseph, “the husband of Mary, by whom Jesus was born, who is called the Messiah” (Matthew 1:16). These names represent real people who lived, struggled through real circumstances, and died.

What makes this especially striking is that many of these figures are not only known from Scripture, but also confirmed by archaeology. For example, a small clay seal impression, known as a bulla, has been discovered bearing the inscription, “Belonging to Hezekiah, son of Ahaz, king of Judah.” Those very names appear in Matthew’s genealogy: “Uzziah was the father of Jotham, Jotham the father of Ahaz, and Ahaz the father of Hezekiah” (Matthew 1:9).

Over the years, archaeologists have uncovered inscriptions, seals, city walls, and artifacts connected to people and places mentioned in the Bible. All of this reinforces Matthew’s point. He is not crafting a legend. He is presenting a record. He is saying that this actually happened.

That matters, especially in a culture that often treats faith as merely personal or subjective. People frequently say things like, “That may be true for you, but not for me.” Matthew’s genealogy challenges that way of thinking. It does not invite us to believe a comforting story. It confronts us with historical reality. God entered time and space. Jesus was born into a traceable family line, under real kings, in a world we can study and verify.

But this genealogy does more than ground the Gospel in history. It also shows us that God has been faithfully at work through that history across generations. When you look closely at Matthew 1, what you see is not just a record of births. You see a record of promises kept.

The genealogy begins with Abraham because that is where the promise takes on a clear covenant form. In Genesis 12, the Lord told Abram, “In you all the families of the earth will be blessed” (Genesis 12:3). That promise did not unfold quickly or easily. It stretched across centuries and generations.

That is why Matthew introduces Jesus as “the son of David, the son of Abraham” (Matthew 1:1). He is drawing a straight line from the covenant God made with Abraham, through the kingship of David, and ultimately to Christ.

Nearly two thousand years passed between God’s promise to Abraham and the birth of Jesus. During that time, God’s people experienced slavery in Egypt, exile in Babylon, and oppression under foreign powers. There were long stretches when it looked like God’s plan had stalled or failed. But it never did.

The genealogy in Matthew 1 is a living timeline of God’s faithfulness. Each name is another marker showing that God kept His word, step by step and generation after generation. Scripture reminds us, “For the Lord is good; His steadfast love endures forever, and His faithfulness to all generations” (Psalm 100:5). Even when God’s people were unfaithful, He remained faithful. Even when circumstances seemed to contradict His promises, God continued to move history forward according to His design.

As we continue through this genealogy, something else becomes clear. It is not only a record of God’s faithfulness, but also a window into the kind of people God chooses to work through. Matthew includes names that would not normally appear in a formal Jewish genealogy. He names several women, and not just any women, but women whose stories include pain, scandal, and brokenness.

He mentions Tamar, whose story involved injustice and desperate action (Matthew 1:3). He names Rahab, a Canaanite woman with a notorious past who trusted in the God of Israel (Matthew 1:5). He includes Ruth, a Moabite widow from a pagan nation who clung to Naomi and to the Lord (Matthew 1:5). And he refers to Bathsheba as “the wife of Uriah,” deliberately reminding us of David’s sin (Matthew 1:6).

Matthew did not have to include these names. The genealogy would have been legitimate without them. But he chose to include them because they make a point. The Messiah’s family tree is filled with outsiders, sinners, and broken people.

From the very beginning, God’s redemptive plan made room for grace. Jesus did not come from a flawless lineage. He came through real lives marked by failure and redemption. The Savior who would welcome sinners came from a line that already reflected that mission.

That is good news for all of us. Every one of us carries stories we would rather not see written down. And yet Matthew shows us that Jesus did not come in spite of those stories. He came through them. God’s grace transforms shame into redemption.

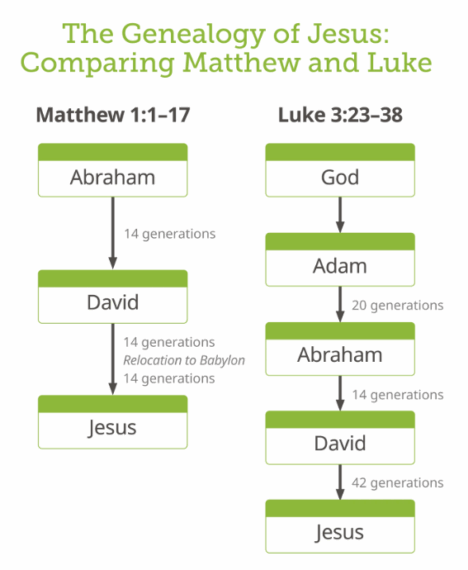

As Matthew brings the genealogy to a close, he draws our attention to its structure. He writes, “So all the generations from Abraham to David are fourteen generations; from David to the deportation to Babylon, fourteen generations; and from the deportation to Babylon to the Messiah, fourteen generations” (Matthew 1:17).

This structure is intentional. In the Hebrew way of thinking, numbers carried symbolic meaning. Fourteen is two sevens, and seven represents completeness and God’s finished work. Three sets of fourteen equal six sevens. That means when Jesus is born, He inaugurates the seventh seven. This is an astonishing claim!

In the Old Testament, the Year of Jubilee was meant to be a time when things were set right again. Debts were to be forgiven. Slaves were to be released. Land was to be returned. It was God’s way of reminding His people that everything ultimately belonged to Him and that He was the One who restores what has been broken (Leviticus 25:10). And yet, Israel never truly lived out the Jubilee as God intended. It remained an unfulfilled picture, a promise waiting for completion.

Matthew is telling us that in Jesus, that long-awaited fulfillment finally arrives. Jesus does not merely announce rest. He embodies it. He is the seventh seven! He is the true Sabbath and the ultimate Jubilee. In Him, debts are forgiven, captives are freed, and what was lost is restored.

That is why Jesus could stand in the synagogue and read, “The Spirit of the Lord is upon Me…to proclaim release to the captives…and to proclaim the favorable year of the Lord” (Luke 4:18–19). Then He closed the scroll and said, “Today this Scripture has been fulfilled in your hearing” (Luke 4:21).

In Him, rest is no longer something we wait for. It is something we receive. When Jesus says, “Come to Me, all who are weary and burdened, and I will give you rest” (Matthew 11:28), He is not offering a pause or a temporary relief. He is offering Himself.

So when we read this list of names, we are not just reading history. We are hearing an invitation. What began with Abraham and reached its fulfillment in Jesus now comes to us. Will we trust the God who has proven Himself faithful? Will we receive the grace He offers and find our rest in Him?